News from the exile collections

Content

- Dr. Vincent C. Frank Steiner (1930–2025) – In memoriam

- Hans Günter Flieg (1923–2024) – in memoriam

- Dr. Ruth K. Westheimer (1928–2024) – in memoriam

- Guy Stern (1922–2023) – in memoriam

- Trude Simonsohn (1921-2022) – in memoriam

- “Child Emigration from Frankfurt am Main. Stories of rescue, loss and remembrance”

- Questionnaires as a source for researching German-speaking exile – using Alfred Kantorowicz as an example

- Professor Dr. John M. Spalek (1928-2021) in memoriam

- Lieselotte Maas (1937-2020) – In memoriam

- Ruth Klüger (1931-2020) – in memoriam

- "What should I cook?" Recipes from the German Exile Archive 1933-1945

- Hellmut Stern (1928-2020) - In memoriam

- Thomas Mann: German listeners! – listening station on the topic of exile outside our Frankfurt building

- Publication of exhibition catalogue “Exile. Experience and Testimony”

- Focusing on the topic of exile – the history magazine "Damals" ("Yesteryear") is published in collaboration with the German Exile Archive 1933–1945

- Dora Schindel (1915–2018) – In memoriam

- Werner Berthold (1921–2017) – In memoriam

- Rolf Kralovitz (1925 - 2015) – In memoriam

- Buddy Elias – In memoriam

- Arts in Exile – virtual exhibition and network

- Brigitte Kralovitz-Meckauer (1925–2014) – in memoriam

- Ludwig Werner Kahn - 100th birthday

- Goethe Medal and honorary membership of the Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V. awarded to Professor John M. Spalek

- "Nestor of German finance" - Fritz Neumark's 110th birthday

- Book donation for the German National Library

- "A prisoner of Stalin and Hitler" - 20 years since the death of Margarete Buber-Neumann

- The founder of futurology – the 100th birthday of Ossip K. Flechtheim

- On the death of lyricist Emma Kann

- Nestor of exile research 1933–1945 in the USA - the 80th birthday of Prof. Dr. John M. Spalek

- Pre-mortem legacy of politologist John G. Stoessinger in the German Exile Archive 1933-1945

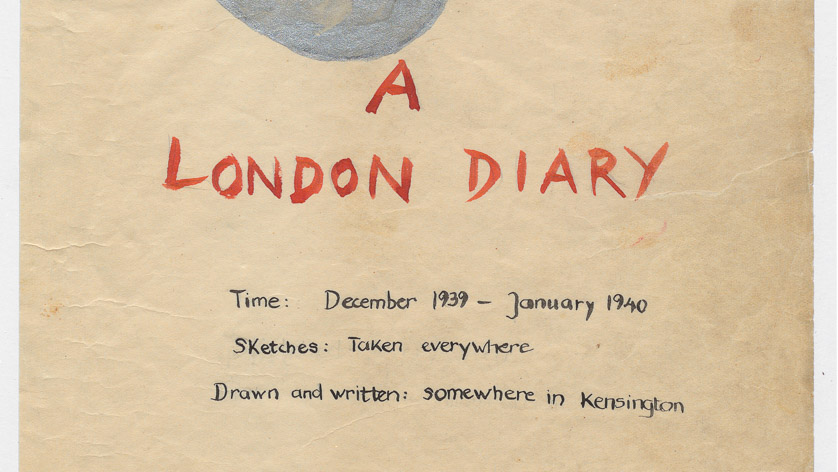

- Lili Cassel Wronker: A London Diary, 1939-1940

- Chronicler of her century – 90th birthday of Anja Lundholm

- Reichsausbürgerungskartei

- Hans Gustav Güterbock

- Geneviève Pitot: The Mauritian-Shekel

Last changes:

11.03.2025